Who are you?

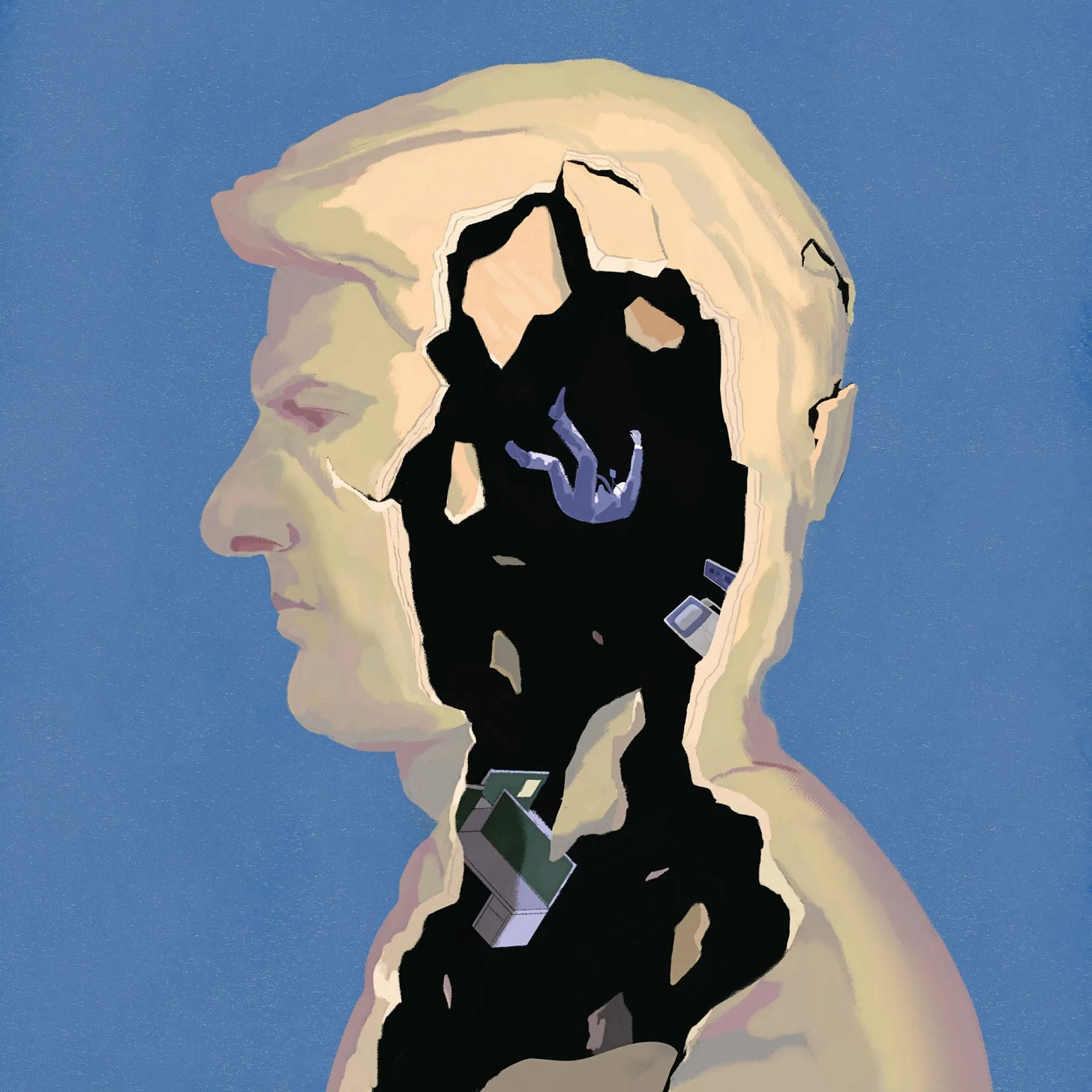

These three words call to you before episode one season one of Severance begins setting the stage for all that is to follow. Severance is, above all, a show about identity and how far you can stretch it before it breaks. Two seasons down, and we’ve found the breaking point.

In the final episode of season two, Mark’s ‘innie’ and ‘outie’ (both played by Adam Scott) talk for the first time. Conversing in start stop fashion through video camera recordings, each personality shares their thoughts, desires, and goals, and for the first time, we see that the two Marks — identical in everything save conscious — could not be further apart. These two separate consciouses, separate identities, are faced with a stone cold reality: there is only one body between them, and they cannot share it equally.

The show’s tension hinges on a groundbreaking procedure called ‘severance’ that splits one person into two different lives through some clever science-fiction-y brain altering surgery. When Mark is at work, he becomes his innie and has no recollection of his out-of-work identity; when Mark is out of the office, he becomes his outie, and he has no idea what happened to him while he was at work. They are, for all extensive purposes, two distinct people trapped in the same body, taking turns being alive.

Up until this point, there has been a tacit agreement between the two Marks. Outie Mark allow his innie a life through going into work, and innie Mark repays the favor by leaving work around dinner time. They weave in and out of existence with their very existence dependent upon the other’s good will. When they have this conversation at the end of season two, the terms of that agreement are threatened, and by the end of the episode, the agreement is broken by innie Mark, who refuses to leave the office, effectively violating outie Mark’s very existence.

In her essay Soul Trader: Identity in a Digital Age,

argues that our understanding of the word ‘identity’ is fairly new — less than a hundred years old. Our current definition arises from the ascendency of technology as a critical part of our everyday lives, so much so our technologies have even become an augmentation of our very beings. Our fingers and toes are no longer the ends of our extremities, our keyboards and buttons are! For some tech speculators, human identity is in for a massive program upgrade, a necessary evolution. Along with the acceleration of individual technologies, our perception of what it means to be human has changed as a side affect. We’ve begun to view humans as technologies that can be tinkered with and improved with the slightest turn of the screw.Contemporary culture tells us that all that matters is “what’s on the inside.” Whether that’s relationships, exercise, careers, or religion, our sensibilities are much more at ease with the notion that inner beauty trumps outer beauty. As a consequence, we devote countless hours time to things like therapy and meditation and thinking and stress and anxiety. We are obsessed with peace of mind because we have been told that it is only in the mind that peace can be found. A common response when one friend asks another friend to go to a party or dinner with them is, “I just really need some me-time right now.” Outside of the mind, there are just too many unpredictable variables. Diving deep within ourselves, we might be able to calm our own seas and find peace. Until you find that peace or acceptance or happiness or whatever-its-called, then you couldn’t possibly enter into the real world of other people.

In his book The Orthodox Way, Bishop Kallistos Ware says, “The body is an integral part of human personhood; the human is not a soul dwelling temporarily in a body. We are a unity of body, soul, and spirit, three in one.” This conversation between the two Marks plainly demonstrates the necessity of the physical body to an individual’s personhood and refutes the notion that all that matters is peace of mind. A person becomes less than a person if they divorce their mind from their body. It is an affront to everything it means to be human.

Walker Percy observed this “abstraction of the body” in many of his books. In Love in the Ruins, a couple named Ted and Tanya go to the doctor because they are struggling to have sex:

The six miles took him five hours. At ten o’clock that night he staggered up his back yard past the barbecue grill, half-dead of fatigue, having been devoured by mosquitoes, leeches, vampire bats, tsetse flies, snapped at by alligators, moccasins, copperheads … set upon by a couple of Michigan State dropouts on a bummer who mistook him for a parent. It was every bit of the ordeal I had hoped…. So it came to pass that half-dead and stinking like a catfish, [Ted] fell into the arms of his good wife Tanya, and made lusty love to her the rest of the night.

The solution offered by the doctor is for Ted to hike home through the woods instead of taking the highway. The entire experience sounds brutal, but you can’t tell me you haven’t felt more aware and alive than after a full day of exhausting exercise. That night the couple made “lusty love.” Their issue had nothing to do with a disease and everything to do with their conviction that they had a problem, a problem that existed in the head not the body.

Returning to Severance. Mark undergoes the severing of his mind from his body as a way to cope with the loss of his wife. He is aimless. Severing his mind and going to work for Lumon is a way to kill time. In effect, severance is a means for him to try and find some kind of peace — even if that peace is simply getting through the days without feeling loss. The effort falls flat as it does not actually address the problem but kicks the can down the road. Mark’s outie remains miserable, even if he is alive for eight less hours in the day.

The unintended consequence of this procedure is the creation of a new conscious — innie Mark, who creates a life of his own at work. He makes friends, finds a purpose, and falls in love. He has something to live for by the end of season two. So when outie Mark discovers that his wife is alive and concocts a plan to break her out of Lumon, innie Mark is hesitant to work with him. Accomplishing his plan means that Mark will never go back to work, and so innie Mark won’t exist. The solution to this problem is another procedure called ‘integration’ where the innie and outie merge their consciousnesses so that they become one, single consciousness. The obvious problem is that how can two people become one. It’s not possible for two people to have full lives when there is own one body to share.

The human body is critical to our identity. If you were to transfer your personability and consciousness to another body, you would not be you anymore. Part of what makes you you is the fact that you are tied to something physical; we are not just spirits floating in the ether, we are flesh and blood. Mark is an experiment in the validity of this statement, and at least thus far in the show, the experiment is failing. Human identity without a body is like water without a container. Innie or outie Mark cannot survive without a body, and if you were to kill Mark, you would kill both personalities. In fact, Mark Scout’s inability to deal with his trauma through physical, bodily means leads to the creation of two personalities and more problems.

The idea of integration is flawed because what Mark has done through severance is an irreversible change to his very being — he’s split himself in two. At the very beginning of the show, Lumon tells him this. The whole motivation behind integration is to merge the two beings into one, but its flawed from the start because you cannot place two into one. To me, this seems to be an unsolvable problem, and the only solution is for one to die.

Mark has, in some ways, created new life, but that life is bastardized by him. He must now face reality: only one can survive, while the other must die.